- Home

- Nicole Evelina

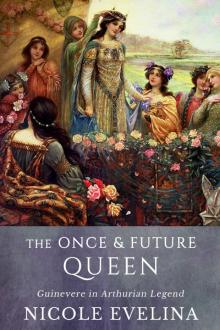

The Once and Future Queen

The Once and Future Queen Read online

The Once and Future Queen

Nicole Evelina

© 2017 Nicole Evelina

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author, Nicole Evelina, or the publisher, Lawson Gartner Publishing, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Lawson Gartner Publishing

PO Box 2021

Maryland Heights, MO, 63043

www.lawsongartnerpublishing.com

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing, 2017

ISBN 978-0-9967632-3-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017915670

Editor: Kelly Gable, Joy Editing

Cover Design: Jenny Quinlan, Historical Editorial

Layout: Nada Qamber, Najla Qamber Designs

Cover Image: Lancelot and Guinevere by Herbert James Draper, 1890s. Image is public domain.

Publisher’s Cataloging-In-Publication Data

(Prepared by The Donohue Group, Inc.)

Names: Evelina, Nicole.

Title: The Once and Future Queen : Guinevere in Arthurian legend / by Nicole Evelina.

Description: Maryland Heights, MO : Lawson Gartner Publishing, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9780996763233

Subjects: LCSH: Guenevere, Queen (Legendary character)--In literature. | Arthurian romances--History and criticism. | Women in literature.

Classification: LCC PN686.G8 | DDC 809.9337--dc23

For Persia Woolley.

Thanks for blazing the trail.

May you rest in peace.

Table Of Contents

INTRODUCTION

Emphasis and Scope

A Note on Names

CHAPTER ONE: An Overview of the Character

Literary Identity vs. Historical Fact

How Many Guineveres Were There?

Guinevere’s Lineage and Family

Guinevere’s Children and Lovers

End of Life

A Changing Woman

CHAPTER TWO: Beginnings: Guinevere in Celtic Literature

Guinevere in Poetry and Literature

Triad 56

Triad 80

Triad 53

Triad 54

CHAPTER THREE: The Middle Ages Part One: Gildas and Geoffrey of Monmouth

Women in the Middle Ages

Life of Gildas

Geoffrey of Monmouth

CHAPTER FOUR: The Middle Ages Part Two: Wace and Layamon

Eleanor as Inspiration

Roman de Brut

Layamon

CHAPTER FIVE: The Middle Ages Part Three: Chrétien De Troyes and Marie De France

Lancelot or The Knight of the Cart

Guinevere and Lancelot as Models of Courtly Love

Chrétien’s Motivations

Marie de France

CHAPTER SIX: The Middle Ages Part Four: The Vulgate Cycle

Importance of the Vulgate Cycle

The True and False Guineveres

Guinevere in The Vulgate Cycle

CHAPTER SEVEN: The Middle Ages Part Five: Alliterative Morte Arthure and Thomas Malory

Alliterative Morte Arthure

Thomas Malory

The Poisoned Apple

Le Morte d’Arthur

Guinevere as Symbol

CHAPTER EIGHT: The Renaissance to The Nineteenth Century

CHAPTER NINE: Tennyson, Idylls of the King

About the Idylls

Guinevere as a Character

Guinevere as a Reflection of Victorian Society

CHAPTER TEN: William Morris, The Defence of Guenevere

Defense or Deception?

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Guinevere in The Early Twentieth Century and T. H. White

Arthuriana for a New Age

T. H. White—The Once and Future King

CHAPTER TWELVE: Guinevere, Victim of the Patriarchy (1960'S—Early 1980'S)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Marion Zimmer Bradley—The Mists of Avalon

Women in the Fore

Guinevere: Christian in a Pagan World

Feminist or Feminot?

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Parke Godwin and Gillian Bradshaw

A New Type of Guinevere

Gillian Bradshaw

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: Sharan Newman

Guinevere as Superwoman

Sharan Newman

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Persia Woolley

“Through the Eyes of a Real Woman”

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Nancy Mckenzie and Rosalind Miles

Guinevere and Elaine

Rosalind Miles

Every Woman a Goddess

Strong, not Feminist

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: Guinevere Post-2000 and Lavinia Collins

The Arthurian Market Slows

Lavinia Collins

The Sexual Side of Guinevere

A Mixed Reaction

CHAPTER NINETEEN: Nicole Evelina

Guinevere and Me: Personal Reflections

Breaking with Tradition by Inventing Guinevere’s Early Years

Pagan vs. Christian

The Dark Side of History

A Woman in a Man’s World

Rejecting the Convent

CONCLUSION

SOURCES

INDEX

BEFORE YOU GO

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Timeline Of Arthurian Fiction Mentioned In This Book

c. 800s – Welsh Triads – (from oral sources; approximate dates first written down, author unknown)

c. 1100-1225 – The Mabinogion (from oral sources; approximate dates first written down, author unknown)

c. 1130-1150 – The Life of Gildas by Caradoc of Llancarven

c. 1136 – The History of the Kings of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth

c. 1155 – Roman de Brut by Wace

c. 1170 – Erec and Enid by Chrétien de Troyes

c. 1170-1215 – Lanval by Marie de France The Romance of Yder (author unknown)

c. 1176 – Cliges by Chrétien de Troyes

c. 1177-1181 – Lancelot, or The Knight of the Cart by Chrétien de Troyes

Yvain, the Knight by Chrétien de Troyes

c. 1190-1215 – Brut by Layamon

c. 1195 – Lanzelet by Ulrich von Zatzikhoven

c. 1200-1250 – The Lancelot-Grail Cycle or Vulgate Cycle (authors unknown)

c. 1200-1210 – Perlesvaus (author unknown)

1220 – Diu Crone by Heinrich von dem Türlin

1268 – Claris et Laris (author unknown)

c. 1400 – Alliterative Morte Arthure (author unknown)

1485 – Morte d’Arthur by Thomas Malory

1587 – The Misfortunes of Arthur by Thomas Hughes

1590-1596 – The Faerie Queen by Edmund Spenser

1801 – The Fairy of the Lake by John Thelwall

1858 – Defence of Guenevere by William Morris

1869 – Idylls of the King by Alfred Lord Tennyson

1956 –The Great Campaigns by Henry Treece

1958 – The Once and Future King by T. H. White

1956 – The Green Man by Henry Treece

1963 – Sword at Sunset by Rosemary Sutcliff

1978 – Lancelot: A Novel by Peter Vansittart

1980 – Firelord by Park Godwin

1981

– Guinevere by Sharan Newman

1982 – In Winter’s Shadow by Gillian Bradshaw

1983 – The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley

The Chessboard Queen by Sharan Newman

1984 – Beloved Exile by Parke Godwin

1985 – Guinevere Evermore by Sharan Newman

1987 – Child of the Northern Spring by Persia Woolley

1990 – Queen of the Summer Stars by Persia Woolley

1991 - Guinevere: The Legend in Autumn by Persia Woolley

1994 – The Child Queen by Nancy McKenzie

1995 – The High Queen by Nancy McKenzie

1998 – Guenevere: Queen of the Summer Country by Rosalind Miles

2000 – The Knight of the Sacred Lake by Rosalind Miles

2001 – The Child of the Holy Grail by Rosalind Miles

2002 – Queen of Camelot by Nancy McKenzie (combined re-issue of The Child Queen and The High Queen)

2014 – Warrior Queen by Lavinia Collins

A Champion’s Duty by Lavinia Collins

Day of Destiny by Lavinia Collins

Guinevere: A Medieval Romance by Lavinia Collins (boxed set)

2016 – Daughter of Destiny by Nicole Evelina

Camelot’s Queen by Nicole Evelina

2018 – Mistress of Legend by Nicole Evelina

Guinevere’s Tale by Nicole Evelina (boxed set)

INTRODUCTION

The name “Guinevere” conjures up evocative images from the pages of literature and the celluloid frames of film. From the long-haired queen weeping in contrition at Arthur’s feet while a heartbroken Lancelot looks on, to the ermine-clad Vanessa Redgrave singing a prayer to St. Genevieve while opining the simple joys of maidenhood, she does nothing by halves. Whether a reader first encounters her in the works of Thomas Malory or in a modern movie or TV adaptation, one thing is clear: Queen Guinevere is a woman to be reckoned with. She will not easily be lost within the pages of history, even if her better-known husband threatens to eclipse her and her reputation is lost in favor of tawdry remembrances of her sin.

History has proven Guinevere will not go down without a fight. Over the last thousand years, she has become a symbol of each society for which she is written, taking on its mores, personifying its deepest fears, and providing a warning: take heed lest you too become a victim of sin. In more recent years, as women have come to demand an equal place in society, she has become a symbol of feminism, the queen who owns her sexuality and isn’t willing to apologize for taking what she wants from life. To some, she is still a man-eater (as T. H. White famously dubbed her), but to others, she is the model of liberated womanhood they so desperately seek.

While the main subject of this book is the evolution of the character of Guinevere, it will also, by necessity, touch upon the roles of women, feminism, and the subject of religion; each is tightly interwoven with how Guinevere is portrayed by her authors. Religion, up until the last century or so, was a vital part of society and the everyday life of most people in Europe and the Americas. As such, it unconsciously affected the way they read Guinevere’s actions and the consequences she deserved. So when the Catholic Church became involved in crafting the Arthurian legend in the twelfth century, Guinevere took on the role of scapegoat for Arthur’s downfall, becoming both a victim of her own lust and the willing perpetrator of evil—the Eve for the world of Camelot. It is only when religion becomes less important to an increasingly secular society that Guinevere begins to be redeemed.

Likewise, the role of women in society was a given until women started to enter the workplace during World War I and later, in the 1970s, began to demand equal treatment outside the home. So it is not surprising that Guinevere started out as a peripheral character who was there to do her husband’s bidding and, at best, entertain his knights. Throughout the Middle Ages and even into the beginning of the twentieth century, women were treated as second class citizens whose role was to serve their husbands and bear children. While Guinevere excelled at the former, being barren, she failed to fulfill one of the key duties assigned to her as a woman and a queen: to bear a child. As such, she is fundamentally tainted, virtually predisposed to evil and weakness, as though she bore an extra original sin that doomed her to an unsavory fate.

As women began to fight for their rights in the 1970s and 1980s, Guinevere slowly emerged from the shadows, becoming a woman with a full backstory, a childhood, opinions and agendas of her own, and a life after King Arthur’s death. With this success as a backdrop, authors of the twenty-first century felt freer to experiment with well-known aspects of the Arthurian story in order to gild their Guinevere with the sex appeal and strength needed to attract an increasingly literature-deficient and mentally-distracted generation.

This is due in no small part to the fact that from the mid-1980s onward, the authors of Guinevere’s story began, for the first time in history, to be predominately female. Women writing the female experience brought a whole new perspective to the character, a well-roundedness that male authors could not hope to achieve. As Sara Cooley notes in her thesis, “it is because these male authors, more often than not, did write women, and wrote them terribly, in ways that are not only frustrating, but also damaging, that we must revisit the canon through a feminist perspective.”1 Elsewhere, she continues, “While we will never know firsthand what it is like to be a queen, or a high priestess, or a knight errant, we will know it better than any man who has ever failed to write us as such”2 or, as any man wrote us as such through male eyes.

Emphasis and Scope

Stephanie Comer very eloquently captures the essence of the idea behind this book: “Guinevere has existed in literature for nearly a millennium, evolving to suit societal values and mores. She has metamorphosed from Arthur’s noble queen to Lancelot’s jealous lover, from a motherly sovereign to a vindictive adulteress as each author struggled to apply his own literary and societal conventions to a character that is both inherited and created.”3 Building upon this idea, this book chronicles the evolution the character of Guinevere has undergone in the last one thousand years of her existence, showing how she changed with the view of women at the time she was written or rewritten to serve as either a warning or a role model for those hearing her story. As Comer notes, “any beginning fiction writer is told the old adage of ‘write what you know…’ [Each Arthurian writer] retold a basic story in terms that they and their readers would understand and relate to. The knights might have been stuck in the quasi-medieval age in which they had been conceived, but Guinevere had the ability to be formed and reformed according to societal standards. She is a barometer, reflecting attitudes and ideas on how society views love, marriage, the battle of the sexes, and, most importantly, women.”4

As it would be impractical to cover in a single book every version of the Arthurian legend in a single designation of time, much less within one thousand years, this volume is limited to the most popular and influential works, those that are most accessible to the average reader with a post-secondary education. This study is also limited to works written for adult audiences, although there has been a resurgence of interest in the Arthurian legend, especially of that focusing on Guinevere, for children and young adult readers in recent years.

While this book focuses on British, French, and American Arthurian portrayals of Guinevere, it is worth noting that the Germans and Spanish also had their own strong Arthurian traditions. “Medieval Arthurian works [appear] in at least 29 languages ranging from Aragonese and Breton to Tagalog, Welsh and Yiddish.”5 In fact, Guinevere is consistently much more positively portrayed in the German tradition than any other. The reason for not including these in the book is simply a matter of controlling the scope. Readers will most likely be familiar with the British, French, and American traditions, so this book focuses on those.

The goal is to bring the evolution of Guinevere out of the halls of academia where she has been intensely studie

d for at least half a century and into the consciousness of everyday readers. There are not many books that attempt to do so. While Andrea Hopkins’ The Book of Guinevere provides a broad overview of the evolution of certain aspects of the character’s personality, it does not cover works more recent than Tennyson, nor does it provide a possible explanation for the character’s change. Therefore, in addition to covering the classic ground of medieval through Victorian Arthuriana, this book will provide a study of the major novels written about Guinevere in the last part of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries and link her growth to cultural and societal influences.

Moreover, there is little information on Guinevere outside of scholarly works written for academics, which the lay reader is not likely to seek out. Thus, this book fills a void by presenting a summation of Guinevere’s treatment since the legend’s inception for a lay audience.

Chapter One will give a broad overview of the character of Guinevere in order to orient or refresh the reader who is not overly familiar with her tradition. Included is a discussion regarding what is known about her from history and literature, the tradition of multiple women named Guinevere in myth, and a summary of what we know of her family, children, lovers, and the end of her life.

In Chapter Two, we examine the earliest extant references to Guinevere to ponder her origins in Welsh poetry and myth, as well as the enigmatic Welsh triads. Though these mentions are brief and Guinevere’s role minor, they provide the fodder on which a thousand years of tradition is built and the basis of many of Guinevere’s less desirable qualities.

Guinevere's Tale

Guinevere's Tale Been Searching For You

Been Searching For You The Once and Future Queen

The Once and Future Queen Madame Presidentess

Madame Presidentess